Zero waste: fact or fiction?

By: Maria Kelleher, P.Eng.

Solid Waste Magazine – 2008-02-01

When I mentioned to a colleague of mine that I was writing an article on Zero Waste he quipped… that’s like Zero Crime — great in principle but it will never happen.

This got me thinking…

This is the first in a series of articles for the year ahead about the various ways we can reach real zero waste (no waste to landfill); in this article I want to set the stage for the broader Zero Waste discussion.

First of all, Zero Waste is not only “no waste to landfill” — it’s more of a philosophy which sets zero waste to landfill as an aspirational goal, and sets the framework to head in the right direction; a framework to reduce waste over time.

The Zero Waste movement was born about 10 years ago by recyclers who realized that a focus on downstream recycling and waste diversion would never get us to a sustainable society. They had to start where goods are created in the first place in order to reduce what’s left to be managed at the tail-end of the system. Zero Waste advocates have described it as a “paradigm shift,” a “journey, not a destination” or (my favorite) “the mother of environmental ‘no brainers’.”

The Zero Waste “journey” has been articulated by different writers and speakers a system to :

* Redesign the way resources and materials flow through society;

* Eliminate subsidies for raw material extraction and waste disposal; and

* Hold producers responsible for their products and packaging from “cradle to cradle.”

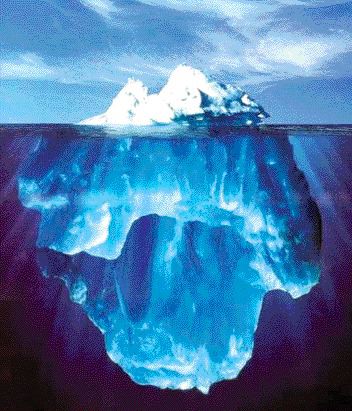

Zero Waste literature quotes a statistic that 71 tonnes of “upstream” waste is produced for every tonne of municipal solid waste produced. This is called the “Waste-berg.”

Zero Waste literature quotes a statistic that 71 tonnes of “upstream” waste is produced for every tonne of municipal solid waste produced. This is called the “Waste-berg.”

Therefore the first step in Zero Waste is to minimize upstream resource extraction to create products. When products are created or required, Zero Waste wants industry-wide redesign of products and process for clean production. As it happens, clean production and lean production have been proven cost effective; therefore, again, this element of the Zero Waste philosophy is a “no-brainer.”

For waste that cannot be avoided, Zero Waste wants society to move from waste management to resource management, or managing waste as a resource.

Finally, Zero Waste communities and companies commit to 90 per cent waste diversion target at “end of pipe.”

Policies and principles

Zero Waste uses four key tools to accomplish its objectives:

*Incentives: Tax the stuff you don’t want and don’t tax the stuff you do want.

*Producer Responsibility and Design For Environment (DfE): Manufacturers are tied legally and economically to end-of-life management of products they introduce to the marketplace.

*Green Purchasing: Force the market to change with the power of spending, and

*Community Building: identify waste as a social and environmental issue.

Businesses that adopt a Zero Waste target generally commit to the following principles and targets:

* Measure performance using the Triple Bottom Line (economic, social and environmental);

* Adopt the precautionary principle (assume chemicals are harmful unless they are proven non-harmful);

* Do not produce wasteful or toxic products;

* Divert >90 per cent from landfill and incineration;

* Direct material to highest and best use;

* Take back products & packaging;

* Prevent waste, plus reuse and repair as much as possible.

Operationalization

Cities and communities that adopt Zero Waste goals operationalize them through a number of means which might not be obvious at first blush, but which are a logical suite of policies within a Zero Waste framework:

* Cities and communities have power over residential waste, therefore they adopt policies that reduce waste (e.g., bag limits, variable-rate pricing);

* Municipalities are large purchasers of products, and can adopt green purchasing specifications;

* Municipalities can impose ordinances such as material bans (e.g., plastic water bottles in Owen Sound) and mandatory recycling on businesses;

* Municipalities have control over building permits, and this is an area where they have significant power to promote Zero Waste through a host of policies such as mandatory per cent diversion plans and imposing deposits on building permits (which are refunded if high diversion can be proven by the builder). The City of Langley, B.C. as well as San Jose and San Diego in California have imposed deposits on building permits — contractors receive their deposit back if they prove they have achieved high diversion levels.

Building waste is one area where cities have power, and increasingly are implementing policies to force reduction of waste at construction and demolition sites. Procurement specifications can stipulate a per cent diversion required: for instance the Greater Toronto Airport Authority stipulated a high diversion target for the demolition of Terminal 1. The successful contractor re-used over 220,000 tonnes of crushed concrete in a separate road construction project. The demolition project eventually achieved 96 per cent diversion.

The Province of Ontario as well as Portland, Oregon, Oakland, California, and Metro Vancouver, B.C. and other communities require waste diversion plan preparation and in some cases source separation at construction and demolition sites. Many cities across North America now require some or all new builds to meet LEED requirements. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) allocates points for six categories of sustainable design: sustainable sites; water efficiency; energy and atmosphere; materials and resources; indoor air quality; and innovation and design process.

While LEED is focused on building materials, energy efficiency and water use, organizations can also earn LEED points through recycling.